Thousands of Union troops overwhelmed Washington at the beginning of the Civil War in 1861. As the Union's most important border outpost, the city became the staging ground for a massive campaign against the South. Virtually all large public structures were quickly repurposed for emergency war needs, beginning with the Capitol, where basement ovens baked bread daily for the city's soldiers while troops upstairs sat at senators' desks and staged mock sessions of Congress.

|

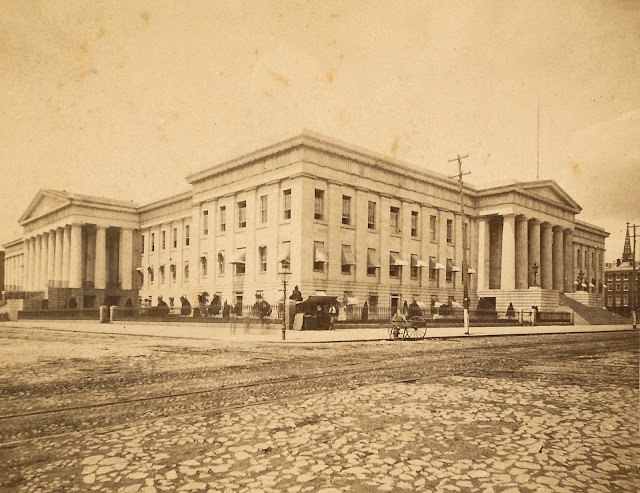

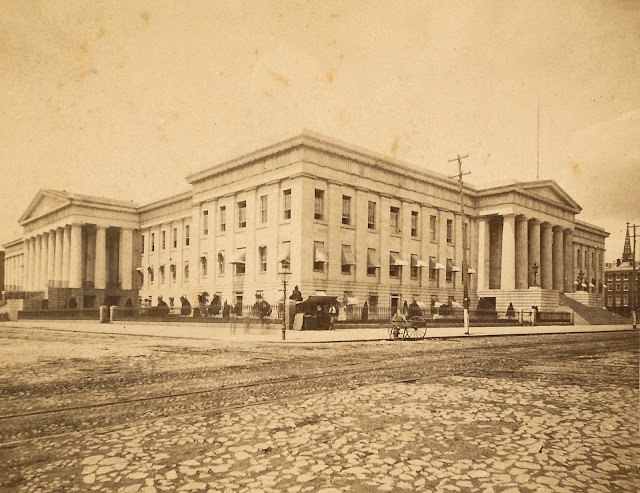

| The Patent Office circa 1870, seen from 7th and E Streets NW. Early streetcar tracks can be seen in the rough cobblestone roadway (Author's collection). |

By this time the Patent Office was almost finished, with final touches underway in the north wing. The completed south, east, and west wings offered spacious top-floor galleries suitable for many non patent-related purposes, the first of which was as a temporary barracks for the First Rhode Island Regiment in March and April 1861. The Rhode Islanders slept in crudely assembled three-tier bunk beds ranged alongside the delicate glass display cases of the West Model Hall. Inevitably, this led to rough treatment of the model displays. Reportedly, some 400 panes of glass were broken, and numerous patent models went missing when the troops left.

In command of the regiment was Colonel Ambrose E. Burnside (1824-1881), an ambitious and genial career military officer and inventor of the Burnside carbine. He would go on to serve as one of the many failed commanders of the Army of the Potomac. Accompanying him and the Rhode Island regiment was the state's "boy" governor, William Sprague IV (1830-1915), the impetuous and fabulously wealthy heir to a textile manufacturing fortune who had been elected governor at the age of 29. Sprague, like many northerners, presumed the war would end quickly and enthusiastically joined his state's troops on their brief and excellent adventure south (as did several of the men's female relatives, who "utterly refused to be left at home," according to

The Evening Star). Pulitzer Prize winning author Margaret Leech, in her magisterial

Reveille in Washington 1860-1865, says Sprague paraded with the troops wearing military dress and a yellow-plumed hat.

Just a block away from the Rhode Island Regiment's Patent Office encampment stood the handsome brick mansion of Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase (1808-1873), on the northwest corner of Sixth and E Streets NW. Living with him was his irrepressible daughter, Kate (1840-1899), who at 21 years of age was the undisputed queen of Washington society—the "Belle of the North," as she was called. Strikingly intelligent, poised, and charming, Kate was also determined to advance both herself and her beloved father, who aspired to the presidency.

|

| Kate Chase, circa 1861 (author's collection). |

Scornful of other women, Kate conquered men's hearts easily, and at a young age she was particularly taken with military men. The onset of the Civil War brought legions of interesting Army officers virtually to her doorstep—the Chases even allowed their own home to be used for recovering wounded soldiers at one point early in the war. Margaret Leech notes that Kate Chase "appeared to be acting in the capacity of hostess at the Rhode Island quarters" in the nearby Patent Office. The Rhode Island regiment had been noted for the high social standing of a number of its recruits, in addition to the rich young governor. While she enjoyed the attention of them all, she had her sights set on the governor. The newspapers' gossip columns soon were publishing rumors of Kate's engagement to Sprague, and she would, in fact, marry him two years later in one of Washington's most celebrated and elaborate fetes.

Meanwhile, the brutal reality of the war soon made itself felt across the city, and nowhere more painfully than at the Patent Office. Unexpectedly high casualties from the nearby Manassas, Antietam, and Fredericksburg battlefields brought a stream of wounded soldiers into Washington. Not long after the Rhode Islanders decamped in early 1861, a temporary hospital ward was set up that quickly grew to fill all three of the Patent Office's finished top floor halls, providing room for hundreds of patients. Though officially designated "Indiana Hospital," most people just called it the Patent Office hospital. President and Mrs. Lincoln paid several visits to the soldiers recuperating there.

And so did poet Walt Whitman (1819-1892), as Garrett Peck describes in his engaging new book,

Walt Whitman in Washington, D.C.: The Civil War and America's Great Poet. Whitman had left his native Brooklyn, New York, in December 1862 to search in Washington for his brother George, who had been wounded in the Battle of Fredericksburg. George turned out to be okay, but Whitman was amazed at all the wounded soldiers that seemed to be everywhere in the capital. "It was the desperate plight of these young men that convinced Whitman to remain in Washington and to help wherever he could," Peck writes. The not-yet-renowned poet took it upon himself to visit soldiers at various Washington hospitals, including Indiana Hospital at the Patent Office, providing food and articles of clothing and helping the soldiers write letters home. Among the press articles Whitman wrote about his activities and later compiled into

Memoranda During The War is this description of the Patent Office:

Feb. 23 [1863].—I must not let the great Hospital at the Patent Office pass away without some mention. A few weeks ago the vast area of the second story of that noblest of Washington buildings, was crowded close with rows of sick, badly wounded and dying soldiers. They were placed in three very large apartments. I went there many times. It was a strange, solemn and, with all its features of suffering and death, a sort of fascinating sight. I go sometimes at night to soothe and relieve particular cases. Two of the immense apartments are fill'd with high and ponderous glass cases, crowded with models in miniature of every kind of utensil, machine or invention, it ever enter'd into the mind of man to conceive; and with curiosities and foreign presents. Between these cases are lateral openings, perhaps eight feet wide, and quite deep, and in these were placed the sick; besides a great long double row of them up and down through the middle of the hall. Many of them were very bad cases, wounds and amputations. Then there was a gallery running above the hall, in which there were beds also. It was, indeed, a curious scene at night, when lit up. The glass cases, the beds, the forms lying there, the gallery above, and the marble pavement under foot—the suffering, and the fortitude to bear it in various degrees—occasionally, from some, the groan that could not be repress'd—sometimes a poor fellow dying, with emaciated face and glassy eye, the nurse by his side, the doctor also there, but no friend, no relative—such were the sights but lately in the Patent Office. The wounded have since been removed from there, and it is now vacant again.

As Whitman notes, the Patent Office hospital finally closed in early 1863. Newer and larger infirmaries, arranged in camp-like pavilions, were being built on the outskirts of the city in the hopes of providing better treatment for the wounded and sick as well as separating them better from the general population so as to limit the spread of contagious diseases.

|

| Wounded and sick at the Armory Square Hospital, 1864. Beds at the Patent Office were likely lined up much like this. (Source: Library of Congress) |

Heavy traffic from army vehicles burdened the Patent Office and its neighborhood, as it did much of the formerly "sleepy" city. In 1862, a reader wrote to

The Evening Star to complain about the teams of horses parked in front of the building at all times ("a string daily is waiting for commissary stores"). The army's teamsters were apparently less than vigilant and would sometimes leave the horses unattended. "Today six wagons were started [i.e., the teams ran off on their own] by the passing of a runaway buggy," the reader wrote, concerned about the safety of the neighborhood's residents.

Perhaps the closing of the hospital in 1863 made life a bit easier for the Patent Office clerks who toiled in the basement on the many patent applications that continued to stream in during the war years. Clara Barton (1821-1912) was one. As the only female clerk, she suffered intense harassment from her insecure male colleagues in addition to the same daily privations they endured, including cold and dampness in winter as well as brutal heat in summer. She worked long hours copying patent applications. "My arm is tired and my poor thumb is all calloused holding my pen," she wrote to her sister-in-law.

Then, in March 1865, all the soldiers and government workers and their grim labors were forgotten for a brief evening of extraordinary glamor and embarrassing excess. "Arguably the single most dramatic historic event to take place in the Patent Office Building was the ball held on the evening of March 6, 1865, for Abraham Lincoln's second inauguration," states Charles F. Robertson in his

Temple of Invention: History of a National Landmark, the authoritative work on the Patent Office building. With victory nearly at hand and the capital in a celebratory mood, the grand inauguration ball was meant to be a shining emblem of the Union's triumph. It was certainly an elegant event, but the war's tensions were not easily set aside.

The ball had been announced in the newspapers as a charitable event, the proceeds of which would go to "the families of our 'brave boys' in the field." Tickets were a hefty ten dollars apiece (roughly $130 in today's money). Each ticket admitted a gentleman accompanied by two ladies. The announcement noted that "An elegant Supper will be served at the Ball, for which no extra charge will be made."

The

Evening Star did its part to play up the event. Despite the fact that tickets could still be purchased in the Patent Office rotunda on the day of the event, the newspaper noted that "The number of distinguished personages in attendance will be very large; and the arrivals of representative belles from all parts of the country with huge Saratoga trunks, indicates, with sufficient distinctness, that the display of beauty and rich costumes will be unprecedented."

Sadly, African Americans were not invited to the fête. The

Daily Morning Chronicle, an organ for the Lincoln administration, ran an obnoxious notice shortly before the ball stating that "there is no truth in the story which has been circulated, that tickets to the inauguration ball have been sold to colored persons. The ball is a private affair, in which the parties concerned have a perfect right to invite whom they please, irrespective of color.... The story, therefore, if not fabricated with a view to injure the success of the ball, may at any time be dismissed as idle and frivolous." In a bizarre twist, several Democrat-controlled newspapers attacked the pro-Lincoln

Chronicle for advocating the exclusion of blacks ("The poor negroes!"), though their shallow, politically-motivated tirades barely hid their lack of genuine concern for African Americans.

Indeed, no African Americans attended as guests. According to

The New York Herald, "The absence of negroes was much remarked. They were so conspicuous during the inauguration ceremonies at the Capitol, and the reception and in the procession... Nobody could have objected, probably, had they been present, for this was a thoroughly abolition ball, all of the old Washington aristocracy refusing to attend. But either the inclination or the ten dollars was wanting, and the colored race was unrepresented." Of course, plenty of African Americans were still present, serving as cooks and waiters.

|

| The East Model Hall was used as the "Promenade Hall" (Author's collection). |

On the evening of the ball, guests arrived on the south side of the building and ascended the grand staircase that led up to the main entrance. There they found the building's large halls elegantly decked out for the affair: "Such another magnificent ball room, supper room, promenade hall, and series of apartments for refreshment rooms, dressing rooms, cloak roams, &c., were probably never before found in conjunction under one roof," the

Star claimed."

|

| Dancing in the North Hall, from The Illustrated London News, April 8, 1865 (Source: Library of Congress). |

From 10pm to midnight guests danced in the great, just finished North Hall, a vast open space lit by gas jets shooting from pipes hung over the crowd. Withers' Band played above them on a temporary raised wooden platform. The blue and white marble tile floor was hard on dancers' feet, especially for the women, and probably limited the amount of actual dancing. By midnight everyone was famished and eager to get their ten dollars' worth of the promised "elegant supper."

And elegant it was. Like the

dinner at the Napier Ball six years before, the banquet was a classic display of Victorian excess. The bill of fare included oysters (provided by the renowned Harvey's Oyster House), terrapin stew, beef a l'anglais, veal Malakoff, boned and roasted grouse, pheasant, quail, venison, pâté de foie gras, tongue en gelée, lobster salad, caramel nougate "with fancy cream candy," almond sponge cake, and endless other cakes, jellies, creams, fruit ices, and chocolates. As was customary, the centerpiece of the buffet spread was an elaborate confectionery sculpture. This one was of the Capitol, high on a pedestal with historical scenes depicted around it.

|

| The official menu for the Inauguration Ball supper. |

The banquet was laid out on a 250-foot stretch of tables in the relatively narrow center aisle of the West Model Hall, a space that could comfortably accommodate about 300 diners. Event planners had failed to devise a way to manage the flow of the 4,000 guests actually in attendance, who all wanted supper at midnight. At first policemen kept the crowd back while the Presidential party was served, and then, according to

The New York Herald, "the doors were thrown open to the guests, who dashed in pell-mell in dreadful confusion, ladies being crushed against the walls, or dragged half fainting through the crush. Men tried to tear down the temporary doorway. The table was cleared almost in a moment, and after the first ten minutes the waiters could bring nothing except for a fee." President and Mrs. Lincoln had been escorted to an upstairs alcove where they could observe the commotion below. "Mrs. Lincoln said it was a 'scramble.' 'Well,' said the President, 'it appears like a very systematic scramble.' This was his only little joke during the evening," the

Herald reported.

|

| Stereoview of the West Model Hall, where the banquet table was set up (Author's collection). |

Supper goers who couldn't get near the food camped out in the alcoves to eat whatever their companions could forage from the tables and bring back to them. These foragers, according to a

New York Times correspondent, "seiz'd upon the most ornamental and least nutritious part of the table decorations, demolished them, carried the pieces off in handkerchiefs or crushed them under foot. Then the more substantial viands were served likewise. Large dishes of choice meats, patettes, salads and jellies were carried off

vi et armis into the alcoves, or elsewhere. One gentleman presented a very ludicrous attitude with a large plate of smoked tongue, requiring both hands to hold it, no place to sit down, and no way to eat it! He looked the picture of despair."

The Evening Star added that "The floor of the supper room was soon sticky, pasty and oily with wasted confections, mashed cake and debris of fowl and meat." The

Herald concluded, "All the dresses which escaped spoliation below were spoiled here. The ladies were very angry—so were the men. Some bullied, some bribed the waiters, and some ate the remains of other people's suppers. The mass surged to and fro like a sea. Plates were broken by dozens. There was a general mess."

The President and his party left around 1am, but many revelers stayed later. When they finally left, they found the great staircase of the south portico lit by "powerful lights from reflectors" that "threw a glare for many squares in every direction," according to the

Star. Hacks and private carriages "were there by the acre, and as far as the eye could reach." The

Star was confident that the ball had been a great success. In succeeding days, editorial opinions were mixed, however. Some newspapers claimed that the event had failed to pay its expenses by several thousand dollars, leaving nothing for soldiers' families. Many critics of the Lincoln administration took pleasure in recounting the melée at the supper table, taking it as an indication of the uncouth nature of the attendees and, by inference, their party. Whatever the case may have been, it was an extraordinary event, a night to remember, though the newly re-instated president would have barely more than a month left to live.

* * * * *

Sources for this article included: Ernest B. Furgurson,

Freedom Rising: Washington in the Civil War (2004); James M. Goode,

Capital Losses: A Cultural History of Washington's Destroyed Buildings (2003); Ernest Ingersoll,

Handy Guide to Washington and the District of Columbia (1897); Kathryn Allamong Jacob,

Capital Elites: High Society in Washington, D.C., after the Civil War (1995); Lucinda Prout Janke,

A Guide to Civil War Washington, D.C.: The Capital of the Union (2013); Sara Amy Leach, ed.,

Capital IA: Industrial Archeology of Washington, D.C. (2001); Margaret Leech,

Reveille in Washington, 1860-1865 (1941); John Lockwood & Charles Lockwood,

The Siege of Washington: The Untold Story of the Twelve Days That Shook the Union (2011); John Oller,

American Queen: The Rise and Fall of Kate Chase Sprague, Civil War "Belle of the North" and Gilded Age Woman of Scandal (2014); Garrett Peck,

Walt Whitman in Washington, D.C.: The Civil War and America's Great Poet (2015); Ben: Perley Poore,

Perley's Reminiscences of Sixty Years in the National Metropolis (1886); Charles F. Robertson,

Temple of Invention: History of a National Landmark (2006); Pamela Scott & Antoinette J. Lee,

Buildings of the District of Columbia (1993); Walt Whitman,

Memoranda During The War (1875); and numerous newspaper articles.

* * * * *

To receive Streets of Washington by email: click on this link and choose "Get Streets of Washington delivered by email" from the Subscribe Now! box on the upper right hand side of the page.

Comments

Post a Comment