8th and H Streets NW -The Calvary Baptist Church

|

| Source: Moore, Picturesque Washington (1887) |

The bushy, thriving trees along H Street—a phenomenon now virtually inconceivable—make this 1886 etching of H and 8th Streets NW seem extraordinarily bucolic. Now on the edge of DC’s small Chinatown, this area was largely residential in 1886. There was no such thing as Chinatown. The trees in the etching obscure the row houses that line the street on either side, so that only the playful children and the church with its stately spire are clearly visible. One hundred and twenty-four years later, the only things that appear unchanged are the street itself and the stately church.

The church is the Calvary Baptist Church, and its meeting house, constructed in 1866, was the first major commission for architect Adolf Cluss. Born in Heilbronn, Germany, in 1825, Cluss learned the architectural trade in his native country, where he also met Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels and became involved in the early Communist movement. Cluss appears to have been a pragmatist, eschewing political upheaval and violence but pushing for workers’ rights and democratic reform. After the failure of German reformist rebellions in 1848, Cluss came to America, soon settling in Washington, D.C., where he got a job as a draughtsman at the Navy Yard. For a time he continued to help organize workers and wrote articles on social reform, but eventually he settled into local politics, development, and, of course, architecture.

|

| The Calvary Baptist Church appears on the left hand side of this stereoview image of 8th Street NW facing south (Author's collection). |

|

| Postcard view of Calvary Baptist Church c. 1910. |

In 1864, when the Calvary Baptist Church’s building committee approached his newly-established architectural firm to design their meeting house, Cluss was already a prominent resident of the German community in Washington, even though he had not yet designed any of his great structures, which would include Center Market, the National Museum building, the Franklin School, Shepherd's Row, and many others. The report of the church’s building committee, read at the new church’s dedication ceremony in June 1866, states that “the committee employed an able architect, who furnished them with a beautiful plan, which, with some slight deviation, was matured into the edifice that now stands before you…. Not a day has been lost for want of funds to carry the work forward, and the cost of the work expanded to more than twice the original estimates.” That exceptionally reliable funding stream was due to the generosity of Amos Kendall, a prominent statesman and successful businessman who had been the principal member of Andrew Jackson’s “Kitchen Cabinet.” Kendall donated $90,000 of the building’s total cost of $115,000.

|

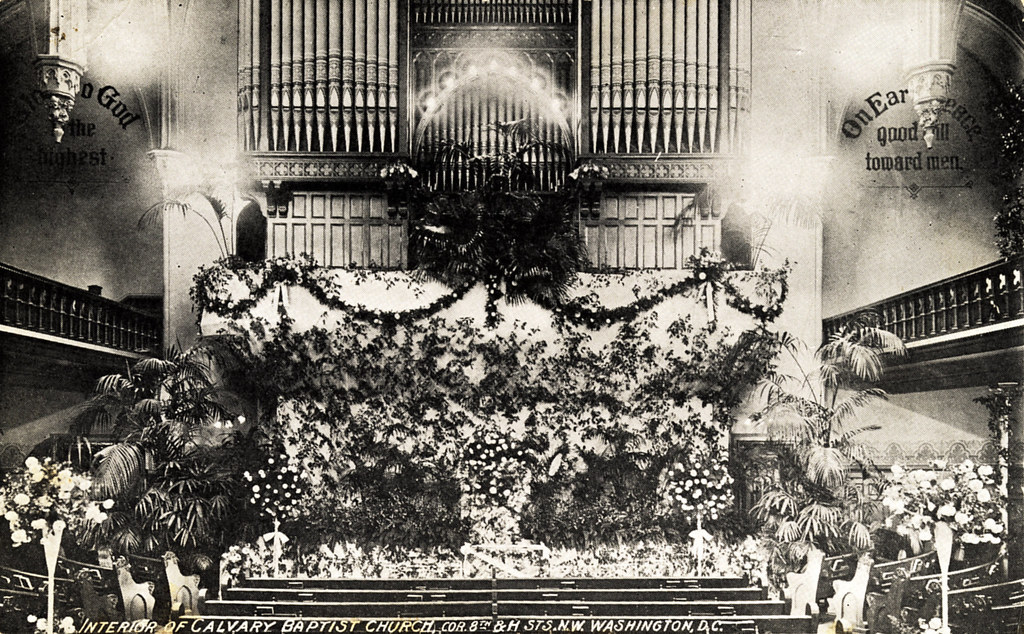

| Postcard of the church's interior circa 1910. |

|

| The church's interior today. |

The congregation, which was formed by abolitionists in 1862 and had never had their own church building previously, worshiped in their beautiful new meeting house for about a year and a half. Then disaster struck. As told by The Washington Times, “On a cold winter night, December 15, 1867, fire was discovered in the new church. The fire department was seriously handicapped by the large amount of snow on the streets and the frozen water. In spite of the most heroic work, the church was soon gutted and burned to the ground. Those who ventured out in the bitter cold saw a sight never to be forgotten. The fall of snow had been quite heavy, and the roof was thickly covered. The flames curled up along the eaves and lit up brilliantly the large expanse of snow.” According to The Evening Star, “the scene, though saddening, was one of rare magnificence, the flames and sparks of fire shooting upward and illuminating the snow flakes, which were falling thick and fast.” However, “by morning the once splendid edifice was a pile of smoking ruins,” the Times reported.

In fact, the tower and two of the church's walls were still standing and were incorporated in the reconstructed building. With money from insurance as well as a substantial additional donation by Amos Kendall, the church was rebuilt and opened again in 1869. That second building still stands today, its pressed red brick now giving it an ironically fiery look. The Gothic Revival style—at the height of fashion in the 1860s—accentuates the building’s height. At 160 feet, its spire was for a time the tallest in Washington. The church's heavily ornamented, Victorian look was originally even more so, the roof being tiled in a pattern of contrasting colors with a line of ornamental crockets gracing its ridge. These apparently were removed when a new roof was installed at some point.

The church carried on relatively unscathed for more than forty years until it was hit by a second great natural disaster, a sudden storm and tornado that wreaked havoc on downtown Washington on the afternoon of July 30, 1913. "Out of a blazing sky, under which the city was sweltering, with the temperature at the 100 point, came the storm roaring from the north, driving a mass of clouds that cast a mantle of total darkness over the town," reported The Washington Post. "The gale, reaching a velocity of nearly 70 miles an hour, swept the streets clear, unroofed houses, tore detached small structures from their foundations, wrecked one office building, overturned wagons and carriages in the streets, and swept Washington's hundred parks, tearing huge branches from trees, and even uprooting sturdy old elms, the landmarks of a century." Most dramatically, perhaps, the gale smashed a huge window in the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and sent shards of plate glass flying through the press room. "Eight or ten women were cut by falling glass, and one printer, John Rhodes, received severe scalp wounds. A hundred or more of the girls working as printers' assistants fainted and fell to the floor, and others dashed terror-stricken for the exits.... While the excitement was at its height, the wind caught a bundle of 1,000 $1 bills, half finished, and swept it through the broken window. The bundle was ripped to pieces, and the bills scattered far and wide." Apparently there ensued a mad free-for-all of men and boys scouring Potomac Park and climbing its tallest trees, frantically trying to grab some of the free money that had rained from the sky—only to discover later that it had no value because it was unfinished.

But, as they say, I digress. The Evening Star later described the storm's impact on the "curious openwork spire" of the Calvary Baptist Church: "A heavy iron casting that capped the steeple was blown off and crashed down on the roof of the Church, smashing many of the slates and otherwise damaging the roof. In addition to this, the steeple was wrenched and twisted until many of spikes that held the iron casting to the wooden framework of the tower were cut off." The wrecked spire was removed and the tower covered over.

|

| Postcard view of the church in the 1940s. |

In addition to the newspapers cited, sources for this article included Lessoff and Mauch, eds., Adolf Cluss Architect From Germany to America (2005) and Wilbur, Chronicles Of Calvary Baptist Church in the City of Washington (1914).

The building is a lovely and striking contrast to some of the more modern buildings in Chinatown and along H Street. Bravo to the church members who were willing to rebuild with the original design in mind. A lesson that too few building owners in Washington never learned.

ReplyDeleteAnd bravo to you for quoting so extensively about the storms. I can almost envision them!

Unfortunately, the interior of the sanctuary has some heavy water damage that only seems to be getting worse (I attend GraceDC, which meets there in the evenings). I hope that the owners of the church will be able to support the necessary repair work, but the relatively small size of the congregation (200 in a space fit for 600) makes me think they won't be able to afford it for some time.

ReplyDeleteAs a member of Calvary, thanks for this post. We have been committed to downtown since our founding.

ReplyDeleteAnd Octavius, you're right about the water damage, but the church membership is growing and with it, our finances. Maybe we should ask Grace DC for some extra help in fixing the leaks. ;-)